Into the Omegaverse: Fan Fantasies on Gender Difference Without Women

Featuring wolf kink, Leo Bersani, Andrea Long Chu, pregnant John Watson, and displaced femininity

Content warning: this essay discusses issues of consent and sexual violence, albeit obliquely and in a fantasy context, as well as explicit sexual content generally. Read carefully!

If you’ll allow me to define scandal loosely, 2019 and 2020 saw two scandals in the parallel worlds of fan fiction and feminist theory. And they are parallel worlds, never the twain shall meet, etc. etc., except that the content of these scandals was unnervingly similar. In order to tell you one story, I want to tell you the other.

In 2019, feminist theorist Andrea Long Chu published her polemical short book Females, which quickly became notorious for its gender-pessimistic thesis: “Everyone is female—and everyone hates it.” By this provocative statement, Chu does not mean that gender or sex don’t exist, or that we truly hate being women. Instead, she says, femaleness is a separate, underlying category, one that shapes the way we relate to other people. “To be female is to let someone else do your desiring for you, at your own expense. This means that femaleness, while it hurts only sometimes, is always bad for you.”

This definition, like so many reality TV contestants of yore, is not here to make friends. It’s a polemic, which is shorthand for “absurd for a reason.” Chu is arguing that beyond the gender conventions that make us different from each other, there’s an underlying subjection, or vulnerability, that we all share. We’re all sissies, at the end of the day. It’s the kind of statement I usually disregard, because I tend to be too distractible for such pessimism. And disregard it I might have, except for the second scandal I want to tell you about.

In 2020, the New York Times found out about something it absolutely should not have. “A Feud in Wolf-Kink Erotica Raises a Deep Legal Question,” the headline read. The article itself concerns a romance novelist, Addison Cain, who published original novels that borrowed tropes from the fan fiction schema “omegaverse.” What really interested The Times was the copyright claims and legal spats that ensued. But it was too late. Omegaverse, which had once been a beloved fandom mainstay, like your favorite wine aunt at Christmas, harmless and voluble but best kept apart from the general public, had gotten loose.

What does wolf-kink erotica have to do with being female, and hating it? Everything, it turns out.

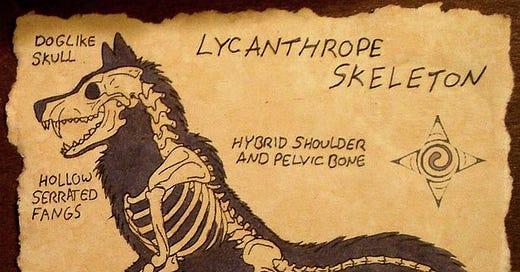

In fan fiction circles, wolf-kink fic is more generally called omegaverse, or Alpha/Beta/Omega Dynamics. It’s an incredibly popular trope, with over 112,000 stories on major fic site Archive of Our Own (AO3) alone. Its origins are shadowy, but most people agree that it began in the Supernatural fandom, one of AO3’s most robust communities. Its rules arose out of an interest in werewolf anatomy and sexual dynamics, but quickly evolved from there. As its name, omegaverse, suggests, this is an alternate universe framework, what fanfic calls an “AU,” and the central alteration of this universe is an additional gender framework that shapes every aspect of identity and intimacy.

In omegaverse, which can be applied to any particular fandom you desire, each person has a secondary gender in addition to male or female: alpha, beta, or omega. These genders come with biological, sexual, and emotional traits. Since these stories are most often about men and gay male relationships, I’ll restrict my explanation to those dynamics. Alphas are dominant, virile, possessive, and well-endowed. Betas are more or less normal and serve little purpose in these stories. Omegas are slighter, with more feminine qualities and a hormonal cycle that makes them “go into heat,” much like dogs and wolves do. In heat, an omega feels a desperate desire for sex, and gives off pheromones that will drive any nearby alpha out of their head with lust.

When the characters give into their mutual hormone fog of desperate fucking, certain experimental features of alpha and omega anatomy come into play; the sex is animalistic and often lasts for days; consent is sometimes foggy, considering the biological drives involved. Sex in the omegaverse also involves a variety of physiological traits and side effects, the details of which we don’t need to get into here. Suffice to say that the male omega partner is always the receptive partner in sex, and that their sexual and biological experience borrows heavily from cis womanhood. The heats, often experienced at regular intervals, mimic the cyclical rhythm of the menstrual cycle. Omegas are subject to chivalry from well-behaved alphas and sexual harassment and violence from menacing ones. Most strikingly, in most omegaverse stories, omega men can become pregnant.

Apart from its interest as a widespread fandom phenomenon, omegaverse is worth studying in conversation with queer and feminist theory for what it offers as a fantasy about gender. Namely, m/m omegaverse stories imagine a version of gender difference without heterosexuality. To go even further, they do gender without women.

This dynamic is most interesting in light of a well-known fact about the fan fiction world: its stories are in large majority about men and are written almost entirely by women and nonbinary people. Why are women—a great number of them queer women—writing with such interest about men and male romance? This question is in some way the guiding interest of this newsletter, and I don’t have one singular answer. But the affordances of omegaverse are more particular. In fact, if I were to make my own more modest polemic statement, not quite up to iconoclast ALC’s standards, it might be: the omegaverse phenomenon is entirely about women, most of all in their absence.

In the omegaverse stories I’ve read, male characters experience cis womanhood in all its vulnerability, fecundity, and pleasure. Even though these men also have traditional male anatomy, their omega status means that they embody gender difference in two central ways. First, they embrace the biological drives of desire with abandon. The worldbuilding of omegaverse emphasizes sexual anatomy and chemistry to an obsessive degree. Take, for instance, this passage from an omegaverse story by Lintilla, based on the BBC show Sherlock, in which John Watson usually lives undercover as a neutral beta:

“Although he could go into heat once every three months – usually lasting three days – John was a cautious man and only allowed himself to indulge once a year. And an indulgence it was. Since puberty, John kept meticulous records of his heat cycles so it was only a matter of abstaining from his hormone suppressant drugs for two days before his predicted heat cycle, and for the next 72 hours, he allowed himself to become the omega that roiled under the surface. Sex during omega estrus was a mind blowing, excessive ordeal that defied all logical thought. During the three days, John would turn away from his carefully cultivated beta persona and transform into a sex god, insatiable and irresistible.”

To be clear, this is a piece of erotic fiction that includes the word “estrus.” I find this self-evidently fascinating. The minor rules of omega biology differ in each story, leaving heat cycles, hormone suppressants, and sexual rhythms to the discretion of each writer. Fantasy worldbuilding, in the omegaverse, means tinkering with biological sex for maximum narrative (or otherwise) gratification.

The second major component of the gender fantasy concerns meditation on a gender power dynamic, where masculinity remains dominant and (male) femininity submits. Much is made of the receptivity of the omega partner, as in this story by infiniteeight, which pairs Clint Barton (aka Hawkeye) and Agent Coulson from the Avengers franchise:

“Maybe it's the heat, or maybe it's Phil, but Clint has never felt so completely filled before. His whole body is hot and loose, accepting every stroke of Phil's cock eagerly, clinging to him slickly as he withdraws. Clint moans and rides the waves of pleasure, rolling his hips into it. He never wants it to stop. Phil's cock is thick and solid and perfect inside him, and the only thing better than having him there, full and hot, is the surge of power and possession that overwhelms Clint every time Phil thrusts into him.”

This story sets up Clint’s omega status over the course of the plot, leading to an intense sexual encounter where omega status become synonymous with more conventional bottoming. Clint feels immense satisfaction at being the submissive partner to an alpha male, on both biological and emotional levels.

You might note that these two dynamics, biological drives and strictly gendered submission, run counter to traditional liberal feminist discourses, which tend to emphasize empowerment, non-gender essentialism, and sexual fluidity. I don’t think we need to hand-wring over the fact that fan fic writers, most if not all of whom would affirm these values in public life, are fantasizing about the inverse online. We can be curious without handwringing, however. It is even possible, I wager, that omegaverse fantasies exceed the respectable bounds of liberal feminism and gesture toward the more threatening and taboo possibilities of queer life.

Omegaverse is, at its core, a fantasy about two related things: submission, and anal sex. Both have a long history as subjects of inquiry in queer theory, ones that some theorists claim have radical potential. In his famous 1987 essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?” Leo Bersani analyzes the homophobic AIDS moral panic, pointing out that representations of infectious gay men recall misogynistic tropes against women, especially sex workers. He writes, “The realities of syphilis in the nineteenth century and of AIDS today ‘legitimate’ a fantasy of female sexuality as intrinsically diseased… Women and gay men spread their legs with an unquenchable appetite for destruction.”

Bersani helped to instigate the “anti-social” turn in queer theory, also called the negative turn, which posits, in laymen’s terms: “they think we’re destroying the social order when we spread our legs? We’re tearing at the fabric of society as they know it? Good. Let’s do that.” He advocates the sometimes-humiliating act of sexual submission as a liberating rejection of everything men are supposed to be. This submission can even damage the stability of identity itself. He borrows from Freud the idea that sexual pleasure coincides with a swell of intensity, “when the organization of the self is momentarily disturbed by sensations or affective processes somehow ‘beyond’ those connected with psychic organization.” In other words, sex, especially risky sex, takes us out of ourselves. There’s pleasure and relief in taking a vacation from being yourself, being in control.

Borrowing from Freud is a dicey endeavor, of course, but this idea took off in queer theory. It’s long become a cornerstone of the field to turn acts and categories usually called shameful, submissive, or dangerous into sources of ecstasy and even badges of political honor. Subsequent generations of scholars have critiqued Bersani’s “fuck it all” attitude. For instance, though he wants to appreciate bottomhood too, Tan Hoang Nguyen points out that queer marginalization, especially when compounded by racism, doesn’t always make you feel very inclined to debase yourself on purpose:

“For those already relegated to the lowest rung of the sexual and social ladder, an unqualified embrace of powerlessness only leads to an amplification of their subjugation and lowly position. What other routes are possible for thinking about gay Asian American bottomhood that would afford pleasure and agency (and, at times, a thrilling surrender of power and agency?)”

Nguyen’s answers for the question became the rest of his book, The View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation. I can’t speak for the racial makeup of fan fic writers, although most of their subjects are white. But I do think that one possible answer to Nguyen’s question “where can we find pleasure, agency, and thrilling surrender all in the same place?” might lie in the world of fantasy fiction. More specifically, I think that omegaverse is a place to find these things for the women who write it. All the pleasure of domination and submission, with none of the baggage of heterosexuality, wrapped up in a pheromone-soaked package. Romance fiction in general, and omegaverse fan fiction in particular, constitutes a masterwork of displaced fantasy.

Bersani himself writes about displacement, arguing that the very definition of sexual desire is the process by which objects of desire “get lost” in the images of satisfaction they create. “Desire, by its very nature, turns us away from its objects,” he writes. This corroborates my thesis, seeming less controversial by the minute, that the omegaverse is about female desire. Women, like the gay men spreading their legs in Bersani’s framework, may want to embrace the self-shattering relief of submission. But in the real life framework of heterosexuality, where women are invariably the omegas, that submission can feel too painful, too true to life.

Consider, for one, this passage from ladyflowdi’s Sherlock omega pregnancy story set in a medieval kingdom:

“[John] presses a hand against his stomach, at the barest hint of roundness, but which would grow and swell and stretch just like Fendon’s had, obscene, ugly, until he was reduced to a defenseless, waddling thing. The omega seam between his legs would open, split, bleed for days, and months from now would dilate to allow for the birth of a child, Sherlock's child, a prince of the Seven Moons. Afterwards Sherlock would get him with child again and again, as many times as was expected of him, and John would have no choice, because he was to bear the generation to come after them.”

The details of this story are a bit shocking in this fantasy context (consider the faux-biological strangeness of a phrase like “the omega seam”), but read more slowly, we can read it as an account steeped in feudal history for royal women. John has become a princely brood mare, and he is subject to the abuses that real women have experienced throughout history. Without the sly displacement of omega manhood, this passage would resonate for women writers and readers in an entirely more literal sense.

Of course, this story develops by having John and Sherlock fall in love, with Sherlock becoming a gallant alpha who protects John, his dignity, and their children. Without this development, the above passage would reflect an entirely negative, vulnerable, painful experience of gendered embodiment. The emotional (as well as sexual) satisfaction of stories likes this depends upon this pattern: posing a threat, and soothing it with love and safety. In this case, the exciting threat of submission and vulnerability, the risk of a sexual experience where “the organization of the self is momentarily disturbed,” as Bersani would have it, and then a developing narrative where that threat is soothed by an trustworthy, loving partner and fulfilling relationship. This is not really a groundbreaking concept; we like to fantasize in fiction, because in fiction we can control the outcome.

If classic queer theorists are on hand to tell us about the personal and political potential of self-shattering sex, feminists really corner the market on understanding fantasy. In Janice Radway’s groundbreaking book Reading the Romance (1982), she explores heterosexual romance novels where the male leads demonstrate cruel or uncaring behavior. These circumstances are so satisfying, Radway posits, because they exist within a narrative structure that eventually gives sufficient reason for that bad behavior, usually excessive, not lacking, romantic feeling on the part of the hero.

In consequence, she writes, “the romance's fantasy ending might defuse or recontain emotions that could prove troublesome in the realm of ordinary life.” In other words, romance fantasy is a safe container for our more transgressive desires, whether for imperious men or animalistic sex. Part of the reason these fantasies are so satisfying, Radway argues, is because they invoke threat: of unkindness, of brutality, of sheer indifference, before disarming these fears with a happy ending. Feminists have been wrestling with this problem, especially in the realm of rape fantasies, for decades. The women Radway interviewed don’t care for them, but Nancy Friday’s 1973 book My Secret Garden is full of women’s hyper-specific rape fantasies. There’s a great Jezebel article about the adjacent “dark romance” genre in the present.

All of these fantasies of submission are interesting in their own right, and, I’d wager, connected. Omegaverse definitely belongs in the conversation, but its rules are different, and so vibrantly contemporary. The fan fiction world is such a queer place, and such a feminine one, where women and nonbinary people are free to fantasize about male sexuality in every possible iteration. The omegaverse fantasy is a trope where women project their own desire for vulnerability onto men, subjecting someone else to it. They recreate a gender hierarchy, based in their own experience, that has nothing to do with them in the realm of the fantasy.

Some gay men have critiqued this habit, pointing out that they don’t exactly have uncomplicated relationships to gender or patriarchy themselves. But if anything, I think omegaverse writers are acknowledging that very fact: the degree to which gender hierarchy can infuse any form of intimacy, what a source of pleasure, pain, or a combination of the two it can be.

This, I think, is what Andrea Long Chu means when she says that everyone is female, and everyone hates it. Nobody, in the personal or political sphere, can be an alpha all the time. Whether we’re in reproductive straight relationships or not, biology structures our lives to some degree, as do so many other forms of power. But I’m most interested in the second part of Chu’s definition. She writes that “femaleness, while it hurts only sometimes, is always bad for you.” In other words, the cost of being alive is subjection, or femaleness, or a crippling omega heat. It’s inevitable. But it doesn’t hurt all the time. The realm of the fantasy is a reprieve not from subjection but from the pain of it. Whether we displace it onto someone else or claim it as ours, we are camping out in the dark night of the gendered soul, lighting little fires.

Next month: a continuation of this exploration, focusing on mpreg (male pregnancy stories) and what they offer as a critique of TERF and anti-surrogacy feminist accounts of pregnancy, birth, and femaleness.

Please consider sharing The Slash with a friend or four! Your tweets and email forwards are much appreciated.

Right now I’m reading:

Cat Sebastian’s Unmasked by the Marquess (don’t be deceived by the hetero cover; it’s a bisexual and trans Regency romp)

Torrey Peters’ Detransition, Baby, for the second time: it’s going to be the coda to my dissertation!

Sarah Schulman’s Conflict is Not Abuse (please commission my essay inventing Eldest Daughter Studies)

My concession to the unavoidable Marvel universe, the wonderful Infinite Coffee and Protection Detail series